Homeschool Life LLC

Volume 1, Issue 3

So, You Want to Homeschool...

What Is Agency and How does it Relate to Motivation?

How many times have you heard a homeschooling parent claim in exasperation, “I just can’t get my kid to do his schoolwork! I have to stand over him until he’s finished!” My usual, calm voiced response is, “I bet. It sounds tiring for both of you.” Then they ask, “How do I get him to do what I tell him? He’s so lazy and unmotivated!”

The holy grail of any endeavor is motivation. Whether it be in business, school, household chores or whatever needs to be done. The lack of motivation typically arises when a task is dull, boring or unpleasant. The scientific literature and research on motivation is extensive and spans not only on psychology, but on neurodevelopment, sociology, behaviorism, cognitive sciences and a host of others. I truly recommend your own pursuit of learning about this major part of human behavior because it is a rich subject that can give you a broad knowledge base and understanding. However, for the topic of homeschooling, I have distilled down a useful element of motivation for you to apply in your endeavors and maybe even to contemplate by yourself with your own struggles in motivation.

If you’ve studied the topic of motivation in psychology, then you are probably aware of extrinsic and intrinsic motivations. You then are also aware that extrinsic motivation such as rewards do not work over time. For this article, let us assume that only intrinsic motivation exists.

Let us now look at something called agency. Agency is the degree to which individuals have the ability to make decisions for themselves. They also have the freedom to control the outcome of those decisions or they may merely have the feeling of control of those decisions. In other words, ask yourself, “Am I free to make rational plans and decisions for my life, and do I have the ability to control and direct the outcome of those decisions?”

It basically comes down to: “Can I do it? Can I own it? Hence, I am responsible for it.”

Agency is created and nurtured in a child’s cognitive development and becomes part of that neuro-scaffolding for the rest of his life. Children need to develop and have practice with agency during their development or their motivation will not develop fully. Children that do not develop agency will typically score low in conscientiousness on the Big 5 personality traits.

So how do children get to exercise and practice agency? The concept of high agency implies an active organism - one who desires, makes plans, and carries out actions. Whereas low agency is hallmarked by a dissociation or an ambiguity between ourselves and the things we do or have done. In other words, agency is not created through telling children what to do, but giving them the freedom to do things on their own. If we are always telling children what to do, how to do it and never allowing them to do things for themselves, how are they going to answer the questions of agency – That is: “Can I do it for myself and am I responsible for the outcome?”

Take this example: Eight-year-old Susan wants a glass of milk. At that age, she should have the strength and dexterity to get a glass, open the fridge, lift and even carry a full carton of milk, and pour herself a glass. This would also include the ability to put the carton back in the fridge and when finished, place the empty glass on the counter. She is both physically and mentally capable to perform these tasks. With some instruction in expectations of where to return the empty glass and acceptable locations to consume the milk, the whole process should require little or no supervision. If this is the case, the child has high agency in this task – Susan can decide and control her environment herself and enjoys the freedom to do it.

However, Jill, who is also eight years old is not allowed to do this task as her mom thinks she is not responsible enough. So Jill must endure an unpleasant conversation from her mother about rules, past failures, being inconvenienced in having to get up to get Jill the milk and then another painful conversation when she finishes her milk. Jill doesn’t own her outcome and she doesn’t have the freedom to initiate a task that she should be capable of. She is not allowed to practice agency. Not only that, Jill’s mother claims she wants Jill to “be responsible” but does not realize that responsibility is just another word for agency’s sense of ownership.

Susan has no problem with the unpleasant tasks of returning the milk, cleaning up minor spills, placing the glass on the counter or even in the dishwasher because she has autonomy in her choices and does not have to rely on others. The truth is that unpleasant tasks (or as some refer to them as responsibilities or chores) are accepted and internalized when sufficient agency is established and not before. If you observe that your child is having problems with tasks, then one probable reason is that he has not practiced, been trained in or given sufficient autonomy/agency in that area.

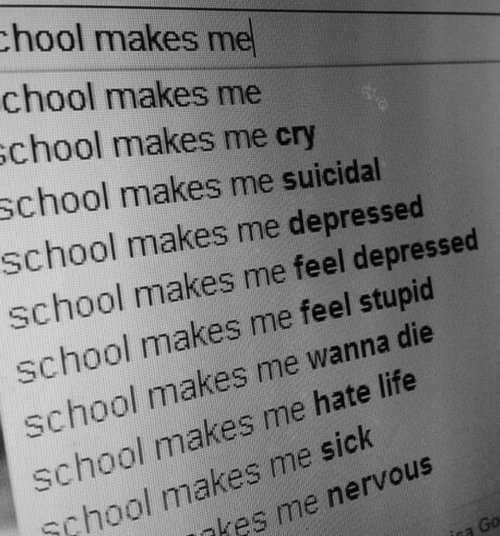

We build agency through all stages and planes of development and not, as some hypothesize, to be set at age 5 or 6. We must observe in our children when they are ready and give them the freedom to fail without berating them for it. It is far better for our children to practice, test and perfect their skills independently within a low-stress environment of loving parents, than in some idealized hard-knock, real-world environment where actual psychological and developmental damage can occur. Parents must become the mentors and guides of their children because that is the most powerful and safest bond. Peer-bonding has its place, but if it plays a dominant role over the parental-bond, then it threatens the relationship between parent and child. When this happens, it doesn’t merely affect the relationship, but also affects every demonstratable agency-based exercise that has been established. This is one reason institutionalized education is so damaging to the strength and natural hierarchy of the family.

We can only build agency through a child’s practice of autonomy. We must observe their particular levels of agency as it is being constructed and adjust our methodology if we observe that our lessons are not serving their intended purpose. Lastly, failure can be a useful and necessary tool, but it must be coupled in conjunction with a child’s autonomy in the practice of agency. In other words, when are children going to learn to manage themselves if you are always micromanaging them?